SPINE - A solo RPG about getting lost in a book

or Siderius Plug’s Immortality in Ninety-nine Endnotes:

In my family, I was taught that books are sacred, something to be read and treated with respect. There was no colouring in books, taking notes in the margins, or making any sort of marks in the book.

It carries forward to this day. When I get an RPG book, I never mark it or highlight it, no matter how much easier it would make running the game. I’ve even passed this message on to my tadpoles.

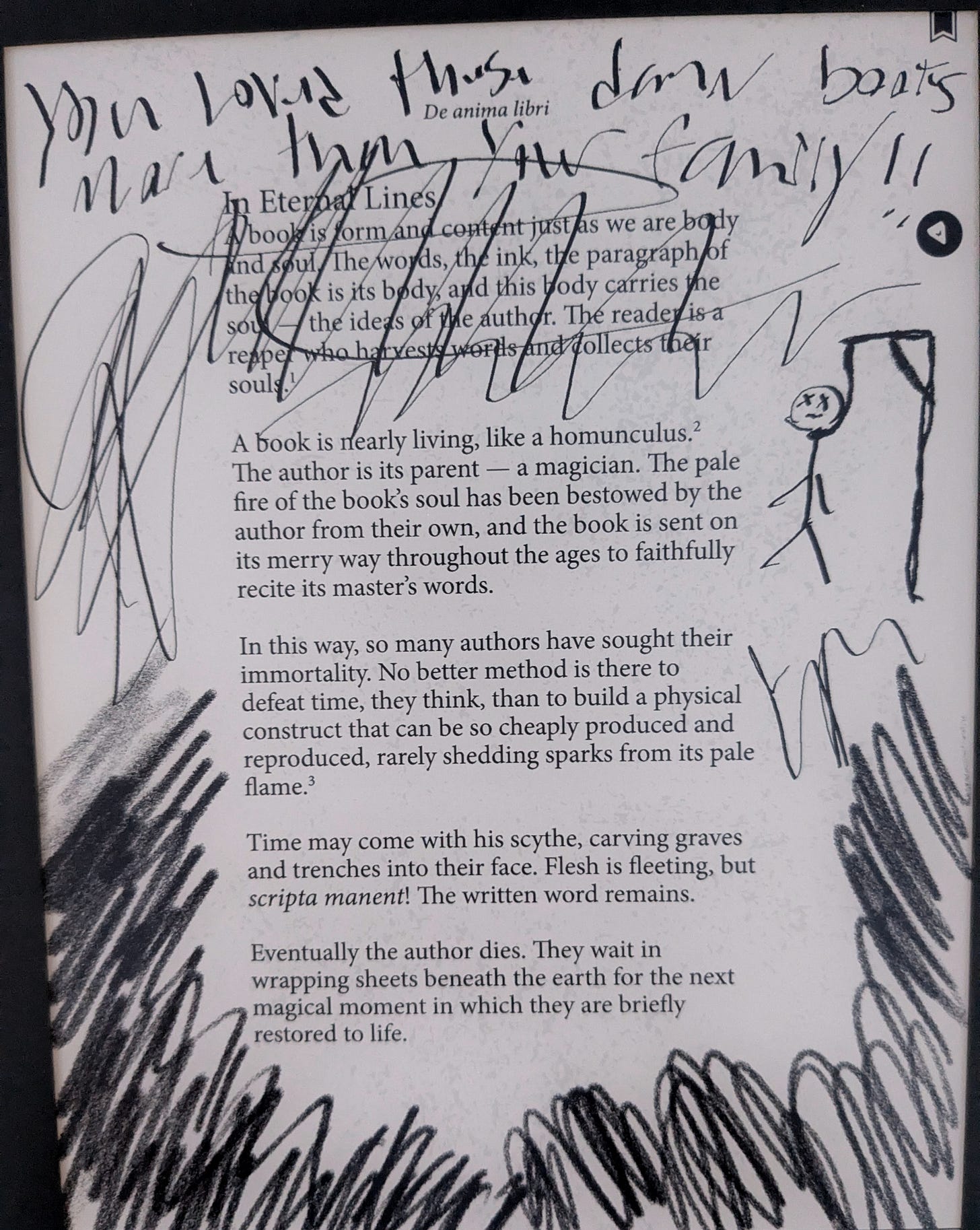

So when I got a copy of Spine by Backwards Tabletop and the first prompt demanded I deface the brand-new book, I was in a bit of shock. The moral dilemma hit me. Do I go against decades of familiar programming? Dare I actually harm a book?

Well, SPINE demanded it, so I started stabbing the book with my pencil.

Summary

🎲 - SPINE - A solo RPG experience

⏰ - Released in 2025

💵 - $0 for the Beta (for now! Hurry!)

🐸 - Solo Built

The Good

Immersive reading/game experience.

Everything you need to play is contained in the book

Feedback

You need to print it out.

Not a traditional RPG (a plus for some)

Assessment

SPINE is an immersive role-playing and reading experience for anyone who enjoys living in the story. Not a ‘traditional’ Solo RPG, this may or may not be a plus for you.

Disclosure: Backwards Tabletop provided me with an early review copy of the Beta.

“Even bad books are books and therefore sacred”

Gunter Grass

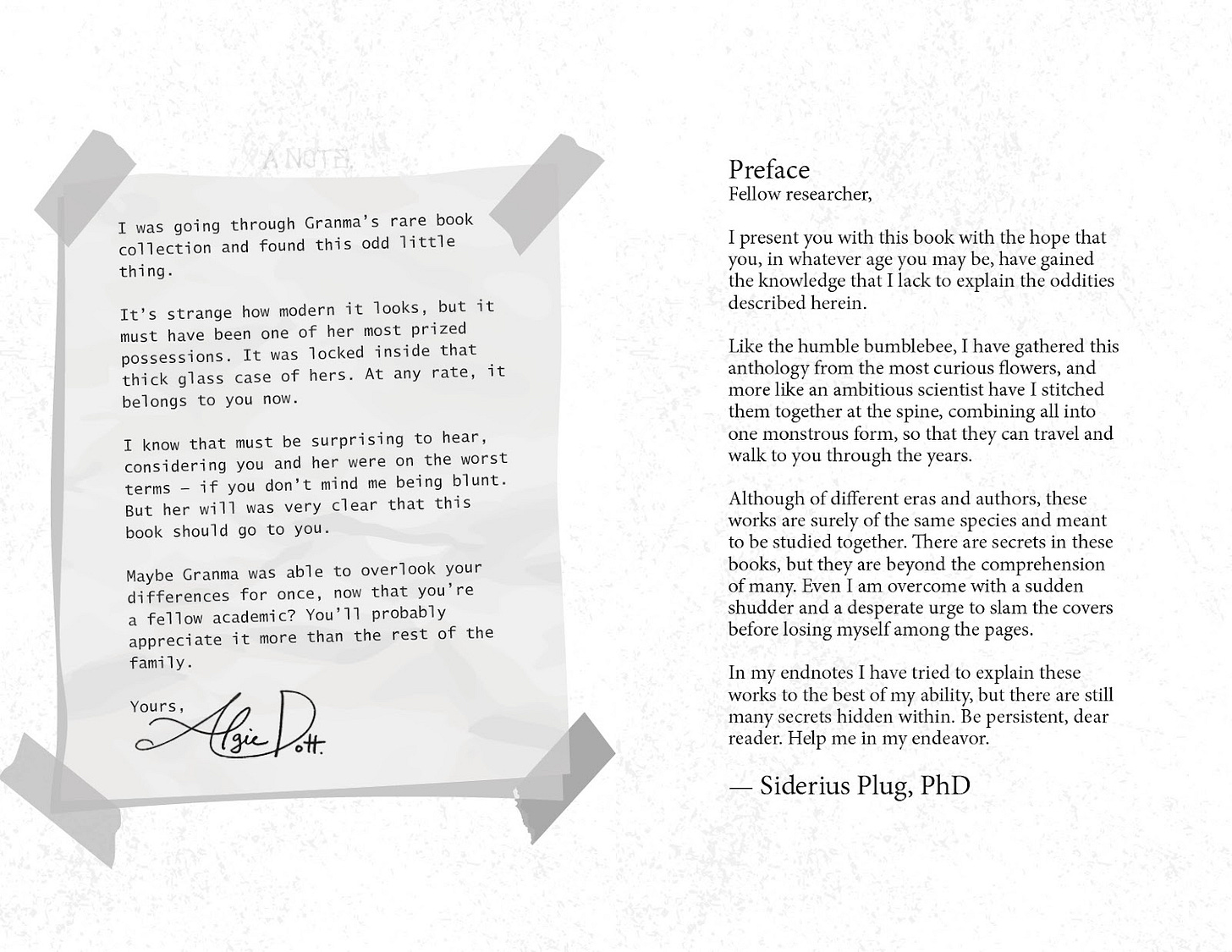

What is SPINE? It’s a good question and one not so easily answered. It’s a book and it’s a game. It’s also an artifact. And a journey. And a story.

It’s a few things. It might be easier to explain how you interact with SPINE.

Spine is meant to be played as a physical book. So you’ll want to print it out (it’s black and white, so it will have mercy on your colour ink) or buy a print-on-demand version (eventually). I played using my Kindle Scribe writing tablet, and that worked ok.

The game/book works like this - start reading the book, and you’ll come across an endnote. Flip to the end of the book and read the endnote and the instructions to you as a player. Then you’ll do the prompt or task and carry on reading.

Sounds simple? That’s where you're wrong, dear reader (I’m joking, keep reading, I love you). A prompt might have you write a brief story of your character’s childhood in the margins. It might have you stab the book with your pencil. It might have you looking for secret meanings in the text.

“A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies. The man who never reads lives only one."

George R.R. Martin

I don’t want to give away too much of the story of SPINE, but it involves complex family dynamics, secret occult rituals and the concept of a soul. Heavy stuff, right? The story slowly unfolds, page after page, endnote after endnote. Each entry will tell just a bit more about the story until a dark story emerges.

The whole concept pulls you in, and by the end of my first play session, I was fighting for my character’s very soul.

"There is no real ending. It's just the place where you stop the story"

Frank Herbert

Spine ends like any other book, once you’ve finished reading it. As a physical artifact, it can now be treated like any other book. Keep it on yourself and pull it down when you want to restart the journey. Give it to a friend, and they can intertwine their story with your story.

How many souls will “Spine or Siderius Plug’s Immortality in Ninety-nine Endnotes” consume?

Interview with Asa from Backwards Tabletop, designer of SPINE

Thanks for taking some time with all the Toadies out there, Asa. Can you tell us a bit about your love for books and what they mean to you?

I love books. I like to lose myself in their stories, to escape into their worlds, to be carried away by words. Books are like little machines — world simulators — with subtle mechanisms that our brains power through reading and interpretation. The main mechanism is language, but a book's layout and its illustrations are mechanisms too.

There's something about printed books that enhances the simulation of these fictional worlds, especially for tabletop RPGs. That tome from D&D 3E is a prop for your wizard. That antique-looking book in your hand is a diary of your vampiric unlife. Physical books insist on their reality. To me, they ground experience within a tabletop RPG in a distraction-free way that I can't always get on an electronic device.

SPINE is not a traditional Solo RPG, in that it doesn’t use dice or tables or character sheets. What about SPINE to you does feel like an RPG?

The lack of dice and tables may signal to some people that SPINE isn't actually a tabletop RPG. Maybe it's a gamebook because you play by reading? Although I disagree with that reasoning, I appreciate where it’s coming from, because SPINE pushes on how we conceptualise solo RPGs as a genre. In contrast, when I say you roleplay as a researcher, respond to prompts in the endnotes, and physically embody your character as you annotate the book, those same people might say that SPINE sounds traditional after all! It's a matter of perspective.

There may not be dice or tables, but there is uncertainty in the endnotes you choose and the prompts that require you to use a random page number that you flip to. There is no character sheet but you write your name in the Ex Libris and you have clocks, wherein you physically depict your likeness over time. The book becomes your character sheet. Designing RPGs is its own form of play, and I think it's fun to defamiliarise these instruments we've come to view as essential for the genre.

SPINE is meant to be gifted to a friend after a couple of playthroughs. What makes SPINE something a player would want to share?

SPINE is a cousin to the “keepsake” style of tabletop RPG, which is a game that produces a memento of your play experience. SPINE invites you to make art with the book, to reauthor it by adding in your own annotations and tearing out pages. Every bit you add will add to the next player’s experience. If you draw a moustache on the Mona Lisa, you change its meaning. It’s not simply the Mona Lisa anymore. In other words, SPINE invites you into the author credits. Then it invites you to share your creation.

If I had my way, I would sell a printed copy of SPINE for $10, and then I would encourage you to play it and sell your used copy for $15. Whereas most material objects depreciate after being used, I honestly believe that each playthrough adds to the narrative value of SPINE.

Also: imagine finding a book in a Little Free Library that’s full of wild annotations! Now that’s a book that would demand your attention…

Part of the challenge of SPINE was that you wrote a book, and you have a whole other story happening in the Endnotes, while also writing prompts for the player to engage with. How did you manage all that and maintain a coherent story?

It seems more complicated than it is. I’ll admit that I’m an arrant thief in that the structure comes from Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, which is a 999-line poem written by fictional poet John Shade with endnotes by fictional scholar Charles Kinbote.

All that I’m doing is relegating the subplot to the endnotes. As far as the prompts go, I’ve focused them on interpretation and encouraging the player to engage with the ambiguities in front of them. Or I’ve focused them on inventing memories that say more about your character than they do about other characters. Simple!

The trick is not making it too obvious or too obscure how the various plots inform one another — also, pacing the delivery of the plot points. For this, I am thoroughly indebted to Furt the Goblin (Book of Gaub, Bridgetown) who is SPINE’s developmental editor and an excellent writer in his own right. Hire him!

On another note, do you have an opinion on the ‘reading RPG books is play’ debate? Which side do you fall on and why?

We underestimate how playful the act of reading is, tabletop RPGs or no. When we read detective fiction, we’re playing. We try to solve the mystery before the detective does. We scrutinize the text for clues.

We do something similar with RPG books. We imagine what it’s like to play as a way to understand the rules. We may even scrutinize language for loopholes. For example, have you ever heard of the peasant railgun? We read during traditional play too. It’s explicitly part of the game, such as referencing rules or reading aloud mini-games.

That’s especially the case in solo games, in which the text itself facilitates our play. We are asked to interpret at every twist and turn. And there are many solo games that invite us to read these prompts playfully.

SPINE is one of those games!

Thank you, Asa, for your time!

Other RPG News

It’s Morktober! Jump into it if you can and make some Mork Borg stuff every day this month. Thank you again to

for leading this movement!

- talks about Emergent Narrative in their solo games.

Next Month

Next month, the Lone Toad is starting a new series of articles called Solo Your Hobbies, where I’ll be looking at how you can bring other hobbies into your solo experience.

I’m also working on a review of the seriously cool Morkin A Lords of Midnight Solo RPG.

Until next time Toad Warriors!

While I understand your long held sentiment that one should never write in a book, and for the most o completely agreed with that sentiment, until I got this hundred year old book from a library in Rhode island. They had a section of books for sale for like a buck, just ancient novels with a bit of wear to them. One book had a little note in it from like the 1930s about the sailor who owned it and where his ship was heading to, it was completely unrelated but something about that was just incredibly wholesome to me.

Spine sounds awesome and I’ve been eyeing Morkin for over a month now! Looking forward to reading your review!